(updated September 2025)

I like talking to strangers. I get a buzz from the connection you can feel from a quick conversation, sometimes just a hello. They’ve even got a name for it – micro-moments of connection. And research says these moments can change your brain in positive ways. It’s also interesting to me to find out what makes people tick. Especially those who are different to me in some way.

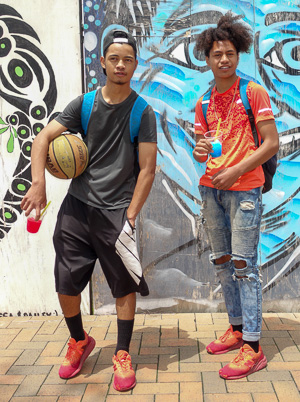

Though I’m far more open about who I connect with in the real world, than I am online, because I have more control and can easily walk away. Like I did the time I saw two people standing in front of a sign that read “The Good Person Test” and my curiosity got the better of me. After introductions they asked if I thought I was a good person.

“Yeah, I think I’m pretty good.”

“Have you ever stolen?”

“Umm, not since I was a child.”

“But that’s still stealing, and do you know what a person who steals is called?”

“A thief?”

Realising the conversation wasn’t going anywhere, I cut it short by asking them to give me a break and walking away. It’s the certainty and black and whiteness that I find off-putting. People like that have rigid ideas about ‘truth’. And they don’t change their beliefs or course of action based on feedback or new knowledge. Nor do they listen. And when someone like that has power, it’s a dangerous combination.

I put the heads of media companies, such as Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg, in that camp as they have a religious like fervor about the way they do things. Except rather than God, they worship money and power.

I remember my excitement when I forayed into social media a little over 20 years ago after joining Old Friends New Zealand, and re-connecting with school mates I hadn’t seen for years. Though my enthusiasm was soon dampened when I connected with someone who turned out to be a stalker.

Then I joined the next big thing, Facebook. That was wonderous and mysterious too. How novel it was to get a post showing what your ‘friend’, who now lives on the other side of the world, was eating for dinner. As the reach of social media grew, so too did my levels of discomfort.

When the Newsfeed appeared in 2006, I started being served inane things that were hardly news and I couldn’t work out why they were put there. Other features soon appeared, including the Like button (social validation). Next came emoticons that initially included an angry face (disapproval, eek). Then people started connecting with anyone and everyone. At one stage, as a way to entice me to engage, they allowed people to poke me and write on my wall! I didn’t like those features either. Maybe because I’ve been poked and prodded enough in my life and sometimes just prefer to be left alone.

Tech gurus, like Mark Zuckerberg (who studied psychology), think they know their stuff about the human psyche. They know about the dopamine hits we get from a like or a positive comment – similar to how we feel after a micro-moment of connection. They know that serving us enticing content will encourage us to click more and stay longer.

Sometimes they get it wrong. As was the case when our every action on Facebook (friending people, updating our profile, etc.) was suddenly broadcast to our friends and it was adrenaline, not dopamine, that our brains got a hit of. There was a lot of push back and it didn’t take long for those changes to be reversed.

That all seems innocuous. I mean what harm is there in being a lab rat. Quite a bit as it turns out. As social media companies increasingly promoted emotive and controversial content (often a more enticing offer than what is true, i.e., boring), things started happening in the real world that were both true and not boring at all. For example, New Zealand had its own version of the January 2021 US Capitol attack, when its Parliament was occupied in March 2022.

These were high profile events that I was aware of. But on reading Max Fischer’s book, The Chaos Machine: The Inside Story of how social media rewired our minds and our world, I learnt that Facebook has an even worse track record in non-English speaking nations.

For example, Facebook enabled the spread of misinformation during the 2015-2016 Zika virus epidemic, which saw many ignore health warnings about its link to severe birth defects. It hosted a Burmese military-led page that fueled the 2018 Rohingya genocide which resulted in over 25,000 deaths. It allowed President Bolsonaro to use social media in a Trump like manner during his 2019 -2022 reign. Amongst other things, he downplayed the Covid-19 pandemic, which resulted in Brazil becoming one of the worst impacted countries in the world.

Just as disturbing as the events themselves is the lack of accountability and even interest in curbing harm. Facebook and many other social media companies don’t have the capability to effectively moderate content in other languages. Not only is this difficult and complicated to do; they don’t seem to care.

Some combination of ideology, greed, and the technological opacity of complex machine-learning blinds executives from seeing their creations in their entirety. The machines are, in the ways that matter, essentially ungoverned.

The Chaos Machine

Social media companies have a legacy of not telling us what they’re up to. We have found out through whistle-blowers and independent researchers who make it their business to know. Despite calls from the UN, world leaders, researchers, and even their own staff to make reforms, they often only do so once backed into a corner. For example, after years of ignoring calls to ban Trump, Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter (now X) only did so after public outrage about his use of social media to incite the Capitol Hill attacks.

This event caused a shake-up of the social media landscape. With the banning of Trump, and other controversial figures, they, and their followers migrated to “alternative” platforms such as Parler, Gab, Telegram and Trump’s very own Truth Social. The likes of far-right extremist Tommy Robinson, who had been banned in 2019, was able to make a comeback as these platforms gained popularity.

The Capitol Hill attacks also generated greater public debate and awareness about the algorithms that Facebook, and other social media companies use to feed us emotive content. And many countries started working on laws, such as the EU’s Digital Services Act 2022, to curb the promotion of illegal content, and disinformation.

With Trump and Robinson[1] back on mainstream sites as of 2023, so too are their followers, many of whom now live in a dual world. They use alternative platforms to seek and share information without restriction. Once misinformation or hate speech becomes group think with emotional charge, it’s then taken to mainstream sites. The superspreaders, such as Robinson, stir up trouble on alternative platforms, then often sit back and let others do their dirty work.

This happened with the far-right riots that spread across the UK. Incorrect claims that the attacker who killed three girls at a Taylor Swift concert (in July 2024) was a Muslim Asylum Seeker were shared on alternative platforms. Facebook and X were then used for a call to action. In this case Robinson also posted to X, using more moderate language than he had been using in the background, to incite violence.

Of late Musk has transformed X into his mouthpiece by pushing his own posts to the forefront. This helped sway the 2024 US election in Trump’s favour. This isn’t democracy. It’s a case of a rich and privileged person misusing their power and having a very misguided belief that they know what’s best for us all. Now that he has fallen out with Trump’s, he continues to use his platform to promote his own political and right wing views.

Early in 2025 Zuckerberg announced his company will no longer take any responsibility for moderation and fact checking. His reasoning; to promote free expression and because “it is too difficult and expensive to do”. [2] Yet Meta’s gross profit last year was over $100b! Instead, this task is being left to users. How, I wonder, will users caution or ban the superspreaders of hate speech for inciting violence.

I also wonder how they will curb AI generated content that falsely portrays people and events, otherwise called “content slop”. Particular when Facebook’s payment model rewards developers of content with high engagement, whether true or not. For example, AI spammers are posting fake images of people in the Auschwitz concentration camp that are attracting millions of views, even though only a few genuine photos of inside the camp exist.1 In terms of history, how will we ever learn from the past if we can no longer decipher fact from fiction.

These latest events have seen alternative and mainstream sites morph into environments that serve up very similar content. I’ve voted with my feet and have walked away from the likes of X and Facebook. This wasn’t difficult as they are places I never felt comfortable in. But unfortunately social media has evolved to a point where I can’t walk away from its influence. The amount of power that billionaire tech gurus have in shaping our world is currently at an all time high.

[1] Tony Robinson has been permanently banned on Facebook but has been allowed back on Twitter (now X)

[2] Transcript: Mark Zuckerberg Announces Major Changes to Meta’s Content Moderation Policies and Operations